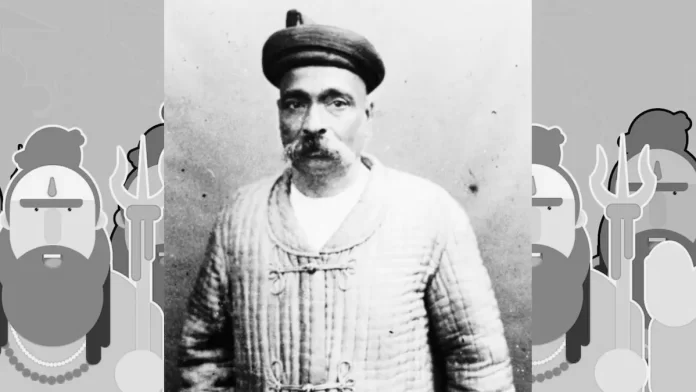

Prime Minister, Narendra Modi on Sunday paid glowing tributes to Bal Gangadhar Tilak on his birth anniversary and said that the story of his courage, struggle and dedication in the freedom movement will always inspire the countrymen.

In this article, we will cover some little known facts about Bal Gangadhar Tilak, one of the tallest leaders of India’s freedom movement before Mahatma Gandhi.

At one stage in his political life he was called “the father of Indian unrest” by British author Sir Valentine Chirol.

Family Background

Bal Gangadhar Tilak was born on 23 July 1856 in an Marathi Hindu Chitpavan Brahmin family in Ratnagiri, Maharashtra. His father, Gangadhar Tilak was a school teacher and a Sanskrit scholar who died when Tilak was sixteen.

Institutions Founded

- New English school for secondary education in 1880 with a few of his college friends, including Gopal Ganesh Agarkar, Mahadev Ballal Namjoshi and Vishnushastri Chiplunkar.

- Deccan Education Society in 1884 to create a new system of education that taught young Indians nationalist ideas through an emphasis on Indian culture.

- Fergusson College in 1885 for post-secondary studies. Tilak taught mathematics at Fergusson College.

Advocated Killing of Oppressors

The strict measures taken by British Government during late 1896 to curb bubonic plague in the Bombay Presidency caused widespread resentment among the Indian public.

Tilak took up this issue by publishing inflammatory articles in his paper Kesari and Maratha, quoting the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, to say that no blame could be attached to anyone who killed an oppressor without any thought of reward.

Following this, on 22 June 1897, Commissioner Rand and another British officer, Lt. Ayerst were shot and killed by the Chapekar brothers and their other associates.

First to propose Devanagari Hindi as National Language

Tilak was the first Congress leader to suggest that Hindi written in the Devanagari script be accepted as the sole national language of India.

During those times, Hindi was largely written in Nastaliq script and also referred to as Hindustani and Urdu.

Tilak’s vehement advocacy of Devanagari Hindu gradually led to the Hindi-Urdu controversy ad that fanned the communal nationalism.

Defended by Jinnah in Sedition Cases

During his lifetime among other political cases, Tilak had been tried for sedition charges in three times by British India Government – in 1897, 1909, and 1916.

During the second sedition trial, Muhammad Ali Jinnah appeared in Tilak’s defence but he was sentenced to six years in prison in Burma.

However, in 1916 when for the third time Tilak was charged for sedition over his lectures on self-rule, Jinnah again was his lawyer and this time led him to acquittal in the case.

Worked for Revival of Hindu-Brahmanism

Tilak believed there needed to be a comprehensive justification for anti-British pro-Hindu activism. For this end, he sought justification in the supposed original principles of the Ramayana and the Bhagavad Gita.

Tilak wrote Shrimadh Bhagvad Gita Rahasya in prison at Mandalay – the analysis of Karma Yoga in the Bhagavad Gita, which is known to be a gift of the Vedas and the Upanishads

Opposed Women’s Rights

Tilak was strongly opposed to liberal trends emerging in Pune such as women’s rights and social reforms against untouchability.

Tilak vehemently opposed the establishment of the first Native girls High school in Pune in 1885.

In 1890, when an eleven-year-old Phulamani Bai died while having sexual intercourse with her much older husband, the Parsi social reformer Behramji Malabari supported the Age of Consent Act, 1891 to raise the age of a girl’s eligibility for marriage.

Tilak opposed the Bill and said that the Parsis as well as the English had no jurisdiction over the (Hindu) religious matters.

He blamed the girl for having “defective female organs” and questioned how the husband could be “persecuted diabolically for doing a harmless act”. He called the girl one of those “dangerous freaks of nature”.

Opposed Intercaste Marriage

Tilak was also opposed to intercaste marriage, particularly the match where an upper caste woman married a lower caste man.

Demeaned Marathas as Shudras

Shahu, the ruler of the princely state of Kolhapur, had several conflicts with Tilak as the latter agreed with the Brahmins decision of Puranic rituals for the Marathas that were intended for Shudras.

Tilak even suggested that the Marathas should be “content” with the Shudra status assigned to them by the Brahmins.

Tilak’s newspapers, as well as the press in Kolhapur, criticised Shahu for his caste prejudice and his unreasoned hostility towards Brahmins.

Indian Historian, Uma Chakravarti states “It is significant that even at the time when Tilak was making political use of Shivaji against Muslims, he refused conceding Kshatriya status on the latter. While Shivaji was a Brave man, all his bravery, it was argued, did not give him the right to a Kshatriya status that very nearly approached that of a Brahmin. Further, the fact that Shivaji worshiped the Brahmanas in no way altered social relations, ‘since it was as a Shudra he did it – as a Shudra the servant, if not the slave, of the Brahmin”.

Started Public Celebration of Ganesha Festival

In 1894, Tilak transformed the household worshipping of Ganesha into a grand public event (Sarvajanik Ganeshotsav) allegedly to annoy Muslims and sow seeds of disunity amongst Marathas and Muslims.

The celebrations consisted of several days of boisterous processions, music, and food. They were organized by the means of subscriptions by neighbourhood, caste, or occupation.

The festival organizers would urge Hindus to protect cows and boycott the Muharram celebrations organized by Shi’a Muslims, in which Hindus had formerly often participated.

Believed in Arctic Home Theory of Aryans

In 1903, Tilak wrote the book The Arctic Home in the Vedas. In it, he argued that the Vedas could only have been composed in the Arctics, and the Aryan bards brought them south after the onset of the last ice age.

Agreement between Tilak and Vivekananda

According to Basukaka, when Swami Vivekananda was living in Tilak’s house as the latter’s guest, it was agreed between the two that Tilak would work for nationalism in the political field, while Vivekananda would work for nationalism in the religious field.

After Vivekananda’s death, Tilak said “No Hindu, he says, who, has the interests of Hinduism at his heart, could help to feel grieved over Vivekananda’s samadhi. Vivekananda, in short, had taken the work of keeping the banner of Advaita philosophy forever flying among all the nations of the world and made them realize the true greatness of Hindu religion and of the Hindu people”.

Concluding Remarks

Overall, Tilak’s fearless stance against British oppression, reflected in his support of actions against oppressors and his involvement in sedition trials, earned him the title “the father of Indian unrest.”

However, His ideas on Hindu-Brahmanism, opposition to social reforms, and demeaning remarks about certain communities also sparked debates and controversies during his time.

While Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s contributions and ideas may have been debated over the years, he remains an integral part of Modern India’s historical narrative rightly or wrongly.