While students of history and politics in India are generally aware of Liaquat Ali Khan as a leader of Muslim League, a staunch advocate of Pakistan movement and Pakistan’s 1st and longest serving Prime Minister, not many are aware about his Rajput family background in Haryana and Uttar Pradesh.

This article shall delve on some unexplored mysteries pertaining to one of the Pakistan’s leading founding father and regarded as Jinnah’s “right hand man” and heir apparent. Read this on till the end to learn more.

Family Background: Rajput, Haryana

Muhammad Liaquat Ali Khan was born on 1 October 1895 into a Haryanvi Ranghar Rajput family in the Karnal, British India (Kazmi 2003).

In the Punjab province of British India, comprising Punjab and some parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in modern Pakistan as well Punjab, Haryana, Chandigarh, Delhi, and some parts of Himachal Pradesh in modern India, 70.7% of the Punjabi Rajputs were Muslims while 27.7% were Hindus, with the highest percentage of Rajputs found in Rawalpindi, with 21% (Sharma, Subash Chander (1987) Punjab, the Crucial Decade).

He was the second of four sons of the wealthy farmer and landlord Rukn-ud-Daulah Shamsher Jung Nawab Bahadur Rustam Ali Khan of Karnal and his wife, Mahmoodah Begum, the daughter of Nawab Quaher Ali Khan of Rajpur in Uttar Pradesh’s Saharanpur’s.

He received his early education in Karnal itself and was courteous, affable and socially popular according to his biographer Muhammad Reza Kazimi.

In 1913, Ali Khan attended the Aligarh Muslim University graduating with a BSc degree in Political science and LLB in 1918.

Later, he also attended Oxford University and was awarded the Master of Law in Law and Justice, by the law faculty.

While a graduate student at Oxford, Ali Khan actively participated in student unions and was elected Honorary Treasurer of the Majlis Society, a student union to promote the Indian students’ rights at the university.

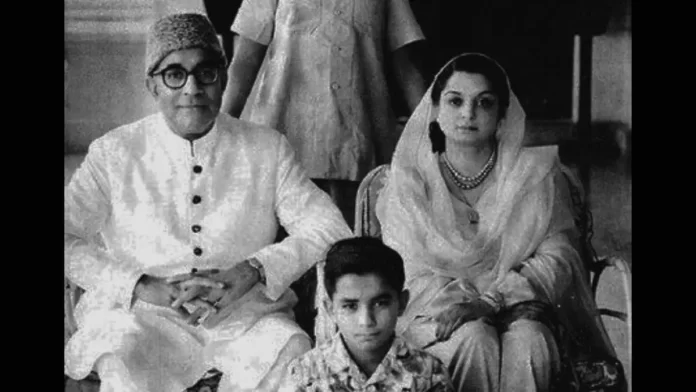

Khan married his cousin, Jehangira Begum in 1918, however the couple later separated few years later.

In 1932, Ali Khan married for a second time to Sheela Pant (born in a Kumaoni Brahmin family) a prominent economist and academic who became an influential figure in the Pakistan movement as Begum Rana and honored as Māder-e-Pakistan or Mother of Pakistan.

Political Role in British India

When Liaquat Ali Khan returned to his homeland India in 1923, Congress leadership approached him to become a part of the party but he politely refused after having a discussion with Nehru.

Rather, he joined the Muslim League under Muhammad Ali Jinnah in 1923 and choose to eradicate to what he saw as the injustice and ill-treatment of Indian Muslims under the British Government.

Soon Jinnah called for an annual session meeting in May 1924, in Lahore where Khan attended and recommended new goals, vision, programmes, for the revival of the party and its greater acceptance amongst Indian Muslims.

Ali Khan was elected to the provisional legislative council in the 1926 elections from the rural Muslim constituency of Muzaffarnagar.

During this time, Ali Khan joined hands with academician Sir Ziauddin Ahmed, taking to organise the Muslim students’ communities into one student union, advocating for the provisional rights of the Muslim state.

In his parliamentary career, Ali Khan established his reputation as “eloquent and principled spokesman” who would never compromise on his principles even in the face of severe odds. Ali Khan, on several occasions, used his influence and good offices for the resolution of communal tension.

Hindu-Muslim Unity: Contradictions

Ali Khan firmed believed against the unity of Hindu-Muslim community, and worked tirelessly for that cause.

In his party presidential address delivered at the Provisional Muslim Education Conference at AMU in 1932, Ali Khan expressed the view that Muslims had “distinct culture of their own and had the right to persevere it”. At this conference, Liaquat Ali Khan also announced that:

“But, days of rapid communalism, in this country are numbered.., and we shall again witness the united Hindu-Muslim India anxious to persevere and maintain all that rich and valuable heritage which the contact of two great cultures bequeathed us. We all believe in the great destiny of our common motherland to achieve which common assets are but invaluable”.

Role as Finance Minister: Most Populist Budget

After the Cabinet Mission 1946, an interim government for United India was formed consisting of members of the Congress and Muslim League.

Muslim League nominees in the interim government included Liaquat Ali Khan (Rajput), Jogendra Nath Mandal (Bengali), Ibrahim Ismail Chundrigar (Gujarati) Ghazanfar Ali Khan (Khokar) & Abdur Rab Nishtar (Kakar).

According to Indian Express, as Finance Minister, Liaquat Ali Khan introduced India’s most populist and reformist budget till date and touted as “poor man’s Budget”.

It radically abolished excise and customs duties on salt (which symbolised colonial oppression) and raised the minimum annual income for taxation from Rs 2,000 to Rs 2,500.

To make up for the revenue loss and to finance additional expenditure (such Rs 40.5 crore for a ‘Grow more Food’ scheme and Rs 17.35 crore on subsidisation of imported food), Khan proposed two new taxes.

- First, a levy of 25% on business profits, including incomes from professions in excess of Rs 1 lakh.

Second, a tax on capital gains above Rs 5,000 from the sale of assets whose prices had recorded substantial increases, particularly during the World War II period.

Khan also doubled the rate of corporation tax from 6.25% to 12.5% (generating another Rs 4 crore), and proposed the “setting up of a Commission to investigate…the great private accumulations of wealth in recent years” from tax-evasion and “black-market operations”.

With all the giveaways and Robin Hood-effect redistributive taxes, Khan was still able to contain the government’s total budgeted expenditure for 1947-48 to Rs 327.88 crore, as against the previous year’s Rs 365.35 crore.

Khan’s budget, the first by an Indian finance minister, was populist but not profligate. While Khan, who was next only to Muhammad Ali Jinnah in the Muslim League hierarchy, defended his budget citing the “principles of social justice” and “the Quranic injunction that wealth should not be allowed to circulate only among the wealthy”, the trade and industry reaction was predictably hostile as prominent stock exchanges shut one after another in massive protest, alarm and panic.

Further, Industrial giants immediately started mounting pressure on Britain and Congress ministers (through the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry, the Birlas-owned Hindustan Times, and the Ramkrishna Dalmia-acquired Times of India, among others) for rolling back the tax proposals.

On March 22, the viceroy, Lord Wavell forced Khan to reduce the business profits tax rate from 25% to 16.25% and treble the exemption limit for capital gains tax from Rs 5,000 to Rs 15,000. Also, the special commission for probing incomes alleged to have escaped taxation did not see the light of day.

However, the capital gains tax that Khan introduced — which he described as a levy on profits in the nature of “unearned increment” as opposed to “ordinary income” — did not, however, go away.

The sections in the Income-Tax Act providing for a tax in respect of any profits or gains arising from the sale, exchange, or transfer of a capital asset, remained on the statute book. It outlived the man who went on to become Pakistan’s first prime minister under Governor General Jinnah.

That being said, there are multiple interpretations of the motives behind Khan’s radical proposals, which he claimed were based on the socialist ideals and declarations of Congress leaders against profiteering by big business.

According to Harish Damodaran, one explanation was that the Muslim League was primarily a party of the landed gentry, peasants and professionals, with little stake in industry and commerce and thus Khan’s budget was aimed at hurting capitalist interests that were overwhelmingly Hindu Marwari and Bania, and who were also the main sponsors of the Congress and British Government.

A second view, he says was that the League had joined the interim coalition in order to sabotage the interim government — and that the budget was essentially a subversive exercise.

According to Damodaran, whether or not these hypotheses were true, Liaquat Ali Khan’s budget may well have accelerated the formation of Pakistan. Many Upper Caste Hindu businessmen and leaders hitherto seemingly committed to the idea of unity of India immediately let go of the Muslim League and accede to the demand for a separate nation.

His Socio-Economic Vision for Pakistan

In 1949 after Jinnah’s death, Prime Minister Khan intensified his vision to establish an Islamic-based system in the country, presenting the Objectives Resolution in the Constituent Assembly and calling it “the most important occasion in the life of this country, next in importance only to the achievement of independence”. Given below are some noteworthy points of the resolution-

- Sovereignty over the entire Universe belongs to God alone and the authority…delegated to the state…through its people for being exercised within the limits prescribed by Him is a sacred trust.

- The state shall exercise its powers and authority through the chosen representatives of the people.

- The principles of democracy, freedom, equality, tolerance, and social justice, as enunciated by Islam, shall be fully observed.

- Adequate provision shall be made for the minorities to freely progress and practice their religions and develop their cultures.

- Pakistan shall be a federation and its constituent units will be autonomous.

- Fundamental rights shall be guaranteed. They include equality of status, opportunity and before law, social, economic, and political justice, and freedom of thought, expression, belief, faith, worship, and association, subject to law and public morality.

- Adequate provisions shall be made to safeguard the legitimate interests of minorities and backward and depressed classes (Pakistan has over 90% reservation)

- The independence of the judiciary shall be fully secured.

- The people of Pakistan may prosper and attain their rightful and honored place among the nations of the world and make their full contribution towards international peace and progress and the happiness of humanity.

Composition of 1st Cabinet

| Office | Name | Caste/Tribe |

| Governor General | Muhammad Ali Jinnah | Baniya |

| Prime Minister | Liaquat Ali Khan | Rajput |

| Minister of Law and Justice | Jogendra Nath Mandal | Bengali (SC) |

| Ministry of Labor and Workers | Jogendra Nath Mandal | Bengali (SC) |

| Foreign Affairs | Chaudhary Zafrullah Khan | Jat |

| Finance Minister | Malik Ghulam (Governor General later) | Jat/Pashtun |

| Ministry of Home/Interior | Khwaja Shahabuddin | Bengali |

| Defence Minister | Iskander Mirza (President later) | Bengali |

| Education and Health | Fazal Ilahi Chaudhry (President later) | Gujjar |

| Science | Salimuzzaman Siddiqui | Jat |

| Minorities and Women | Sheila Irene Pant | Brahmin |

| Communication | Abdur Rab Nishtar | Kakar/Pashtun |

Assassination Mystery

On 16 October 1951, Khan was shot twice in the chest while he was addressing a gathering of 100,000 at Company Bagh (Company Gardens), Rawalpindi.

The police immediately shot the presumed murderer who was later identified as professional assassin Said Akbar.

Khan was rushed to a hospital and given a blood transfusion, but he succumbed to his injuries. Said Akbar Babrak was an Afghan national from the Pashtun Zadran tribe.

The exact motive behind the assassination has never been fully revealed and much speculation surrounds it. An Urdu daily published in Bhopal, India, saw a US hand behind the assassination.

Upon his death, Khan was given the honorific title of “Shaheed-e-Millat”, or “Martyr of the Nation”. He is buried at Mazar-e-Quaid, the mausoleum built for Jinnah in Karachi.

The Municipal Park, where he was assassinated, was renamed Liaquat Bagh (Bagh means Garden) in his honor. It is the same location where ex-Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto (also a Rajput) was also assassinated in 2007.

Criticism of Liaquat Ali Khan

The Daily Times, a leading English-language newspaper, held Liaquat Ali Khan responsible for mixing religion and politics, pointing out that “Liaquat Ali Khan had no constituency in the country, his hometown was left behind in India. Bengalis were a majority in the newly created state of Pakistan and this was a painful reality for him”.

According to the Daily Times, Liaquat Ali Khan and his legal team restrained from writing down the constitution, the reason being simple: The Bengali demographic majority would have been granted political power and, Liaquat Ali Khan would have been sent out of the prime minister’s office.

The Secularists also held him responsible for promoting the Right-wing political forces controlling the country in the name of Islam and further politicised the Islam, despite its true nature.

Overall Legacy: Positive or Negative?

Liaquat Ali Khan is Pakistan’s first and longest serving Prime Minister. He was next only to Muhammad Ali Jinnah in the Muslim League hierarchy. His legacy was built up as a man who was the “martyr for democracy” in the newly-founded country.

Many in Pakistan saw him as a man who sacrificed his life to preserve the parliamentary system of government. After his death, his wife Sheela Pant (Rana Begum) remained an influential figure in the Pakistani foreign service, and was also the Governor of Sindh Province in the 1970s.

Popularly, he is known as Quaid-i-Millat (Leader of the Nation) and Shaheed-i-Millat (Martyr of the Nation). His wife Sheela Pant is also revered as Mandar-e-Pakistan or Mother of Pakistan.

Their honored status and acceptance by Pakistani Muslims and State (alleged for its extreme hostility towards Hindu-Brahmins) clearly shows that in Muslim societies and polities, belief-based brotherhood, unity and obligations often triumphs over parochial racial, caste or tribal instincts.

With power and honor comes responsibility and accountability. So in the same vein, they (not Islam or Muslims in general) should be held responsible for the problems of Pakistan in terms of its socio-economic development and hot-cold relations with Bengal and India because they (not the scholars of Islam) created Pakistan and charted its domestic and foreign policies.

That being said his assassination was a first political murder of any civilian leader in Pakistan, and Liaqat Ali Khan is remembered fondly by most Pakistanis. In an editorial written by Daily Jang, the media summed up that “his name will remain shining forever on the horizon of Pakistan”.

In Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan is regarded as Jinnah’s “right hand man” and heir apparent, as Jinnah once had said. His role in filling in the vacuum created by Jinnah’s death is seen as decisive in tackling critical problems during Pakistan’s fledgling years and in devising measures for the consolidation of Pakistan.