In our daily lives, we encounter a barrage of arguments and reasoning, often in the form of debates, discussions, or persuasive messages.

While some arguments are well-founded and logically sound, others are plagued by errors in reasoning and fallacies.

Recognizing and understanding these bad arguments is essential for critical thinking and effective communication.

In this article, we’ll explore a comprehensive catalog of common types of bad arguments or reasoning, providing examples to illustrate each one.

Ad Hominem Fallacy

The ad hominem fallacy occurs when someone attacks the person making the argument rather than addressing the argument itself.

Examples:

- You shouldn’t listen to Mr. X. After all, he comes from a community full of traitors.

- You shouldn’t listen to John’s advice on dieting. He’s overweight and has no self-control.

- You’re not a historian; why don’t you stick to your own field.

- You don’t really care about lowering crime in the city, you just want people to vote for you.

Appeal to Fear Fallacy

This fallacy employs fear to manipulate people into accepting an argument.

Examples:

- Mr. Dog lost the elections after Mr. Donkey convinced everyone that that if Mr. Dog becomes the President than soon enough the entire nation would be run by Dogs.

- If we don’t pass this law, crime will skyrocket, and your family will be in danger.

- I ask all employees to vote for my chosen candidate in the upcoming elections. If the other candidate wins, he will raise taxes and many of you will lose your jobs.

Appeal to Irrelevant Authority Fallacy

An appeal to authority relies on the testimony of an authority figure rather than providing evidence or reasoning.

Examples:

- Astrology was practiced by technologically advanced civilizations such as the Ancient Chinese. Therefore, it must be true.

- People used to sleep for nine hours a night many centuries ago, therefore we need to sleep for that long these days as well.

- Dr. Smith, a renowned physicist, said that climate change is a hoax, so it must be true.

- Professors in Germany showed such and such to be true.

Appeal to the Bandwagon

According to Ali Almossawi, also known as the appeal to the people, such an argument uses the fact that a sizable number of people, or perhaps even a majority, believe in something as evidence that it must therefore be true.

Examples:

- Members of x community only vote for members of x community. Therefore you should also vote for your own community members in the upcoming elections.

- All the cool kids use this hair gel; be one of them.

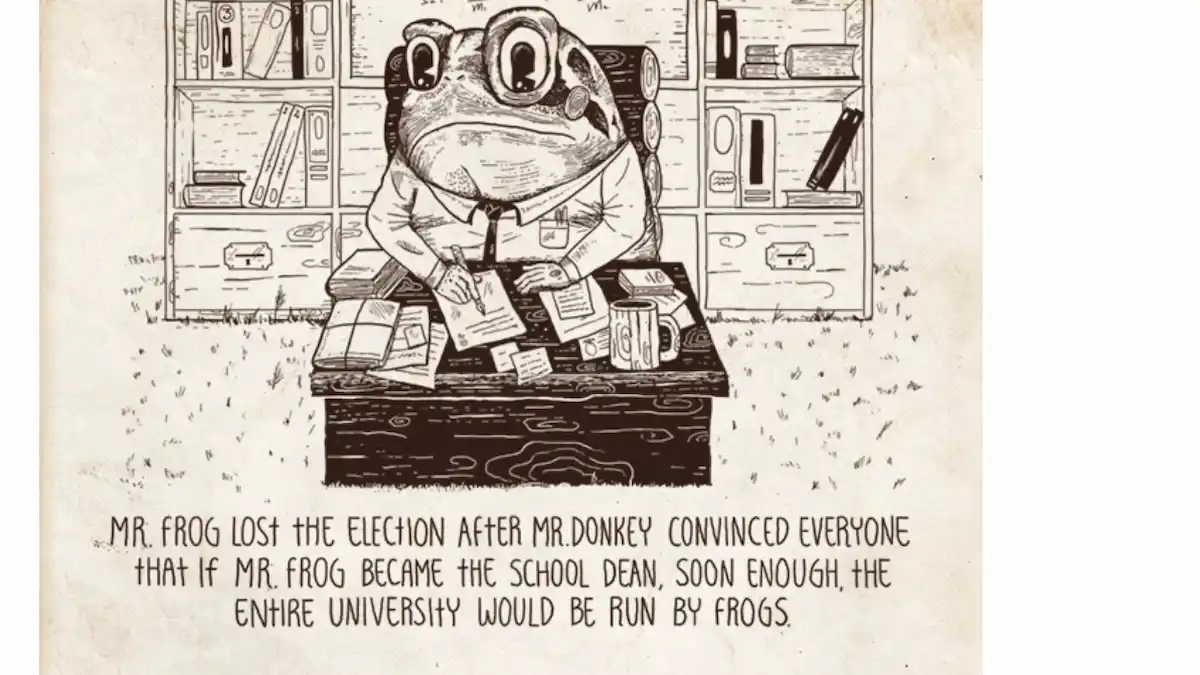

Slippery Slope Fallacy

This fallacy argues that a small first step will inevitably lead to a chain of related negative events.

Examples:

- If we allow same-sex marriage, next people will want to marry animals or objects.

- We shouldn’t allow people uncontrolled access to the Internet. The next thing you know, they will be frequenting pornographic websites and, soon enough our entire moral fabric will disintegrate and we will be reduced to animals.

Appeal to Tradition Fallacy

This fallacy assumes that something is better or more valid simply because it’s traditional.

Example: “We’ve always done it this way, so it must be the best way.”

False Dilemma Fallacy

This fallacy presents an argument in such a way that it simplifies a complex issue into only two options.

Examples

- You’re either with us or against us in the fight against terrorism.

- In the war on fanaticism, there are no sidelines; you are either with us or with the fanatics.

- Cold War and Non-Aligned Countries

Straw Man Fallacy

This fallacy involves misrepresenting an opponent’s argument to make it easier to attack.

Examples:

- Samantha argues for stricter environmental regulations, but that would cripple our economy. We can’t all be tree huggers like her.

- My opponent is trying to convince you that we evolved from monkeys who were swinging from trees; a truly ludicrous claim (Ali Almossawi).

Equivocation Fallacy

According to Ali Almossawi, equivocation exploits the ambiguity of language by changing the meaning of a word during the course of an argument and using the different meanings to support some conclusion.

A word whose meaning is maintained throughout an argument is described as being used univocally.

Examples:

- How can you be against faith when we take leaps of faith all the time, with friends and potential spouses and investments?

- Science cannot tell us why things happen. Why do we exist? Why be moral? Thus, we need some other source to tell us why things happen.

Appeal to Ignorance Fallacy

This fallacy suggests that a statement is true because it hasn’t been proven false or false because it hasn’t been proven true.

Example:

- There’s no evidence that aliens don’t exist, so they must exist.

- It is impossible to imagine that we actually landed a man on the moon, therefore it never happened.

Circular Reasoning (Begging the Question)

Circular reasoning occurs when the conclusion is restated within the premise, making it appear valid without providing evidence.

Example: “The Bible is true because it’s the word of God, and we know God exists because the Bible says so.”

Post Hoc Fallacy (Correlation vs. Causation)

This error in reasoning asserts that because one event follows another, the first event caused the second.

Example: “I ate ice cream before my exam, and I passed. Therefore, eating ice cream improves test scores.”

Hasty Generalisation Fallacy

Hasty generalization occurs when a conclusion is drawn from insufficient or biased evidence.

Example: I met two rude people from New York, so all New Yorkers must be rude.

Red Herring Fallacy

A red herring is a distraction that takes the argument off course, often by introducing irrelevant information.

Example: We need to address climate change, but first, let’s talk about the economy.

Appeal to Emotion Fallacy

Appeal to emotion relies on emotional responses rather than logic or evidence to persuade.

Example: “Buy this product, and you’ll be happy, loved, and fulfilled.”

Texas Sharpshooter Fallacy

This fallacy occurs when someone cherry-picks data or evidence to support their argument while ignoring contradictory information.

Example: “Look at all these successful people who dropped out of college. Therefore, dropping out of college leads to success.”

Anecdotal Evidence Fallacy

Anecdotal evidence is based on personal experience or isolated examples and is often used to generalize a broad claim.

Example: “My uncle smoked for 90 years and lived a long life, so smoking isn’t harmful.”

No True Scotsman Fallacy

This fallacy involves modifying a claim to exclude specific cases that challenge the argument’s validity.

Ali Almossawi gives the example of a Scottish person reading a newspaper and comes across a story about an Englishman who has committed a heinous crime, to which he reacts by saying, “No Scotsman would do such a thing.”

The next day, he comes across a story about a Scotsman who has committed an even worse crime; instead of amending his claim about Scotsmen, he reacts by saying, “No true Scotsman would do such a thing.”

Examples:

- No true Scotsman would do such a thing.

- No true environmentalist would ever use plastic bags.

- No true upper class man can assault a lower class girl (Pratap Misra vs State Of Orissa 1977).

Tu Quoque Fallacy (Whataboutism)

Tu Quoque redirects criticism or blame back onto the accuser, implying that their argument is invalid because they are also guilty of the same thing.

Example: “You say I shouldn’t speed, but I’ve seen you speeding too.”

Burden of Proof Fallacy

The burden of proof fallacy shifts the responsibility to disprove a claim onto the opposing party rather than the one making the claim.

Example: “Prove to me that unicorns don’t exist.”

Genetic Fallacy

The genetic fallacy involves dismissing an argument based on its origin or source, rather than evaluating its merits.

Examples:

- This scientific theory was proposed by a convicted criminal, so it can’t be trusted.

- Of course he supports the union workers on strike; he is after all from the same village.

- With all respect your highness, how can we entertain the idea of a dog who developed his ideas while on the street?

Guilt by Association

According to Ali Almossawi, guilt by association is discrediting an argument for proposing an idea that is shared by some socially demonized individual or group.

- My opponent is calling for a healthcare system that would resemble that of socialist countries.

- We cannot let women drive cars because people in godless countries let their women drive cars.

Composition and Division Fallacy

The composition fallacy assumes that what is true of the parts is true of the whole, while the division fallacy assumes the opposite.

Example: Composition – “This car has excellent parts, so the whole car must be amazing.” Division – “Since the team is strong individually, they must be the best team.”

The Fallacy Fallacy

The fallacy fallacy claims that an argument is false because it contains a fallacy.

Example: “John’s argument is flawed because it uses the straw man fallacy.”

Conclusion

Understanding these common types of bad arguments and reasoning is essential for critical thinking and effective communication.

Recognizing when these fallacies are being used in discussions, debates, or persuasive messages allows us to approach arguments with skepticism and seek out well-founded, logical conclusions.

By sharpening our ability to spot bad arguments, we not only protect ourselves from faulty reasoning but also contribute to more meaningful and productive dialogues in our personal and professional lives.

More: An illustrated book of bad Reasoning by Ali Almossawi.